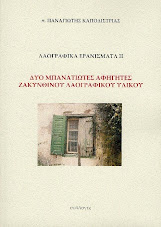

Ο Πάπας Φραγκίσκος προλογίζει το βιβλίο, με τίτλο: «Υπενθυμίζοντας το μέλλον: Προς μια Εσχατολογική Οντολογία» του αείμνηστου Μητροπολίτη του Οικουμενικού Πατριαρχείου, Περγάμου Ιωάννη (1931-2023).

«Τον Ιωάννη Ζηζιούλα», γράφει ο Πάπας, «τον πρωτογνώρισα το 2013, όταν καλωσόρισα την Αντιπροσωπεία του Οικουμενικού Πατριαρχείου Κωνσταντινουπόλεως που ήρθε στη Ρώμη για την εορτή των Αγίων Πέτρου και Παύλου». «Ήταν, σημειώνει, «μια συνάντηση που επιβεβαίωσε για μένα την πεποίθηση για το πόσα έχουμε ακόμη να μάθουμε από τους Ορθοδόξους αδελφούς και αδελφές μας σχετικά με την επισκοπική συλλογικότητα και την παράδοση της συνοδικότητας».

Και ο Πάπας Φραγκίσκος επισημαίνει: «Το έσχατον χτυπά την πόρτα της καθημερινότητάς μας, αναζητά τη συνεργασία μας, λύνει τις αλυσίδες, ελευθερώνει τη μετάβαση σε μια καλή ζωή. Και είναι στο επίκεντρο του ευχαριστιακού κανόνα ότι για τον Ζηζιούλα η Εκκλησία «θυμάται το μέλλον», συμπληρώνοντας, όπως κάνει στα κεφάλαια αυτού του βιβλίου μια δοξολογία σε «Αυτόν που έρχεται»”.

Ακολουθεί αυτούσιος ο πρόλογος του Πάπα στην αγγλική γλώσσα, όπως δημοσιεύτηκε στην ιστοσελίδα vaticannews.va, αλλά και στην σχετική έκδοση:

“To hold this book by John Zizioulas, Metropolitan of Pergamon, in my hands is for me still to clasp his hands in the friendship that bound us together. A posthumous book, as the title tells us, it comes to me as a sign springing from a past that has been liberated in the Future of God.

I first met John Zizioulas in 2013 when I welcomed the Delegation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople that came to Rome for the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. It was a meeting that confirmed for me the conviction of how much we still have to learn from our Orthodox brothers and sisters with regard to episcopal collegiality and the tradition of synodicality.

In our conversations during successive meetings, he often brought up the topic of an eschatological theology that for years he had been hoping to turn into a book. When we prayed and reflected on the unity of Christians, he communicated his realism to me: this would only be achieved at the end of the ages. But in the meantime, we had the duty to do everything possible, spes contra spem, to continue to search for it together. The fact that it would be achieved only at the end should not feed complacency or find us idle: we had to believe that the Future was already in operation, “the cause of all being.” A Future that comes toward history, that does not emerge from history. Not simply the end of the journey, but a companion in our life that is capable of “coloring” it with the colors of the Resurrection and with the voice of the Spirit that would have “remembered new things.” He avoided the danger of our having our gaze fixed on a past able to make us prisoners, prisoners above all of old errors, of failed attempts, through accumulating negative junk, through encouraging the implanting of mistrust. We all suffer the negativity of looking backwards, and the sincere search for the unity of all Christians suffers from this in a particular way. The value of our traditions is to open up the path, and if instead they close it, if they hold us back, that means that we are mistaken in the way we interpret them, prisoners of our fear, attached to our sense of security, with the risk of transforming faith into ideology and mummifying the truth that in Christ is always life and way (John 14:6), path of peace, bread of communion, source of unity.

The eschaton knocks at the door of our daily life, seeks our collaboration, loosens the chains, liberates the transition to a good life. And it is at the heart of the eucharistic canon that for Zizioulas the Church “remembers the future,” completing as he does in the chapters of this book a doxology to “Him who comes,” a theology that he has written on his knees, in expectation.

I want to awake the dawn (Psalm 108:2). The psalm’s verse calls on all the instruments and voices of humanity to cry out our need for God’s Future. Let us awake the dawn within ourselves, let us awake hope. Indeed, “the substance of things hoped for” (Heb 11:1), the gesture that constitutes Christianity, is to give a sign, a tangible and daily sign, a humble and disarmed sign, of “Him who is and who was and who is to come” (Rev 1:8)”.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου